‘Who could thrive where?’ Imagining resettlement as a cooperative mobility strategy

Mobility is crucial for refugees to leave conflict zones and reach safety. Nonetheless, there are not many regular options for refugees to cross borders and enter third countries. Resettlement is one of them.

Resettlement, however, is not simply a phase of mobility between a transit and a host country but a crucial step in setting the course for sustainable long-term integration. Currently there seems to be a gap between the design of resettlement programmes on the one hand and integration strategies on the other: States and the UNHCR plan and organise resettlement and placement processes, while hosting municipalities, civil society and (former) migrants and refugees are key actors in shaping reception and integration on the ground. They do not, however, play an active role in resettlement processes themselves.

In an overview study of resettlement programmes, the European Migration Network (EMN) describes national resettlement schemes as ‘tailor-made’ solutions. But as long as national resettlement is dominated by the selection criteria of host States, the question arises of whom these programmes ultimately serve.

Can resettlement address the needs of refugees and hosting municipalities alike and thus set the stage for integration without offering them options to participate in shaping the resettlement process?

My research focuses primarily on state-led resettlement programmes to Europe, which offer (the potential for) a higher number of resettlement places but less scope of action for host communities and refugees than private sponsored resettlement. I identify limited transparency, exclusionary decision-making, and narrow spaces for local ownership by refugees and host communities as focal challenges. However, there are also good practice examples all over Europe demonstrating why policy makers should consider rethinking resettlement as a cooperative mobility strategy: increasing transparency, matching refugees’ individual potentials and needs with local integration offers, and strengthening the democratic basis of resettlement. Local community ownership can for example tighten links between resettlement and integration processes and may ultimately render the latter more sustainable.

Recognising transparency as a precondition for cooperation

In the face of a multitude of resettlement programmes and national selection criteria, both refugees and host communities find it difficult to gain access to the information relevant to their respective situations. This creates a high level of uncertainty, which is problematic insofar as research shows that even in such a context refugees develop strong preferences for specific destination countries.

Many refugees may have heard of resettlement to the United States. But how many of them have had the chance to learn about new programmes concerning Belgium or Lithuania?

Better access to reliable information on resettlement programmes can help refugees form realistic expectations about possible futures, thereby increasing their capacity to contribute to placement processes that are sensitive to their needs and potential.

Once selection processes are completed, early pre-departure orientation is a vital tool of information and expectation management. In order to offer refugees sufficient information without unnecessarily prolonging the resettlement process, it is essential to tailor pre-departure and post-arrival orientation to refugees’ needs.

Good practice includes peer support and input from host communities: the Netherlands engage resettled refugees as advisors in pre-departure orientation via Skype; in Sweden, municipal representatives contribute to cultural orientation programmes; and through the SHARE Network, several smaller municipalities have created short videos to present themselves to soon-to-arrive and newly-arrived refugees.

Not only refugees but also host municipalities can benefit from better information on resettlement processes. European local authorities criticise that they are often informed about pending arrivals at very short notice and are provided with little detail on the specific needs of the newcomers. An interesting exception to this practice is the Norwegian Cultural Orientation Programme NORCO. Implemented by the International Organization for Migration, it prepares refugees for resettlement and offers seminars for Norwegian municipalities to inform them about arriving refugees and their respective situations.

Combining municipal integration offers with refugees’ potential and needs

With paragraph 34 of the Global Compact on Refugees, signatory States recognise the importance of including refugees and host communities in the development of durable solutions. This is echoed through the SHARE Network, which engages European municipalities in resettlement debates and peer-learning, and highlights that placement should take into account both refugees’ needs and potential as well as local integration offers.

However, for refugees resettlement is currently presented as a binary choice, where the main option for agency is the rejection of a resettlement offer. Furthermore, in many EU countries, municipalities neither have the opportunity to voice their interest in resettlement nor reject participation in national schemes. Finland provides a noteworthy exception of good practice, where municipalities engage in resettlement on a voluntary basis, which led to a municipal reception commitment exceeding the national quota in 2018.

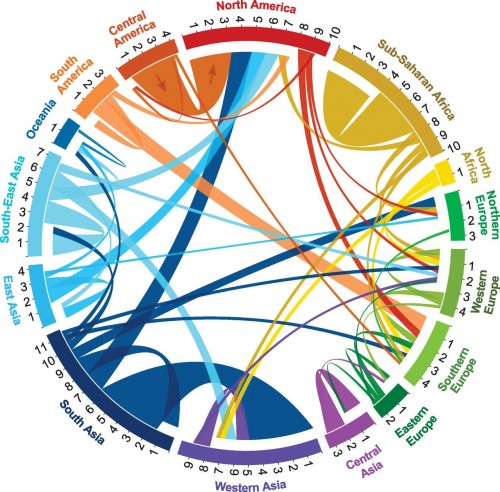

Based on the idea that refugees and host municipalities could improve resettlement processes through proactive engagement and positive choices, matching tools are currently under development to support placement decision-making. Cooperation between displacement research, economic theory and AI-technology has given rise to innovative instruments such as the AI-powered software Annie™ MOORE developed by the University of Oxford in the UK, the University of Lund in Sweden, and the Worcester Polytechnic Institute as part of the project ‘Refugees.AI’. The project strives to operationalise the assumption that

Valuing local ownership

Some European municipalities even wish to go further than simply presenting reception offers. In 2015, the transnational municipal network EUROCITIES called upon the EU, Member States as well as UNHCR to include local authorities in resettlement planning and decision-making, stating that resettlement could only be successful if local circumstances were taken into account. The growing interest of the EU and its Member States in private sponsored resettlement demonstrates that national and supranational institutions recognise the potential of local public and private actors to connect resettlement and integration strategies. Enabling the local level to play a more active role can create a local sense of ownership in host communities and increase democratic legitimacy of resettlement processes while fully respecting States’ national sovereignty.

As many local authorities interact closely with civil society and citizens on questions of integration and social cohesion, strengthening local engagement in resettlement processes could also open up new options to cooperate with (resettled) refugees and learn from their first-hand experience. The municipal SHARE Network has therefore established a ‘Resettlement Ambassador Programme’ in cooperation with UNHCR and the European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE) in cities such as Antwerp, Munich and Paris.

Conclusion

Resettlement and integration processes should go hand in hand. By excluding key resettlement actors, namely refugees and host municipalities, from shaping resettlement processes, national decision-makers deprive themselves of valuable expertise and implementation potential. Good practice all over Europe shows that municipalities, refugees, States, and international organisations can cooperate in order to increase transparency, match individual potentials and needs with local offers, and strengthen local community ownership.

Rethinking resettlement as a collaborative mobility strategy may thus open up possibilities to explore the question of “who could thrive where?” instead of restricting refugees’ choices to “yes or no” and municipalities’ input to “how many are coming?”