Rethinking the Controversies of Deportation

In 2018, thousands of people who had come to the UK from the Caribbean as migrant workers or their dependants in the 1950s and 1960s found themselves caught within a pervasive net of immigration enforcement measures. These measures, contained in the 2014 and 2016 Immigration Acts, were employed to create a ‘hostile environment’ for irregular migrants. Unable to provide evidence of continuous residence in the UK for the past 40+ years, many of these people were threatened with deportation – despite having arrived legally in the UK.

Known as the ‘Windrush scandal’, these events shocked the British public. The fact that these people were predominantly black and had arrived from British ex-colonies as part of the ‘mother country’s’ post-war economic reconstruction efforts adds important dimensions to diagnosing the controversies of deportation in the real world. It requires scholars to place issues of discrimination and historical injustice at the centre of their analysis.

Rethinking Deportation: Between Past and Present

Deportation – understood as the forced expulsion of individual non-citizens from the territory of the state – poses some crucial ethical and political challenges to the liberal state. These concern the definition of membership in the state, the legitimacy of different forms of mobility, and upholding standards of procedural justice. Mainly rooted in a liberal perspective, scholars engaging with these issues have largely overlooked the ways in which deportation is related to discrimination and histories of injustice. However, as the Windrush scandal demonstrates, these issues remain relevant today.

In this piece, I contribute to rethinking the controversies of deportation in a way that highlights the relationship between deportation, discrimination, and the legacy of historical injustice. Rather than looking at abstract theorizations of deportation, I ground my analysis on the arguments of those who have contested deportation in practice. Drawing on my doctoral research on the evolution of anti-deportation activism in the United Kingdom, I discuss historical examples of civil society of contestations of deportation from the late 1970s to the mid-1990s.

How can these historical contestations help us rethink the controversies of deportation in the UK today? Firstly, I argue that theorists should look further into how deportation reproduces a discriminatory logic of who has access to mobility. Secondly, I point out that deportation creates particular forms of discrimination at the level of enforcement. Finally, I show that deportation has the potential to reproduce historical injustice towards particular groups of contemporary migrants.

The Relationship Between Deportation, Discrimination and Mobility

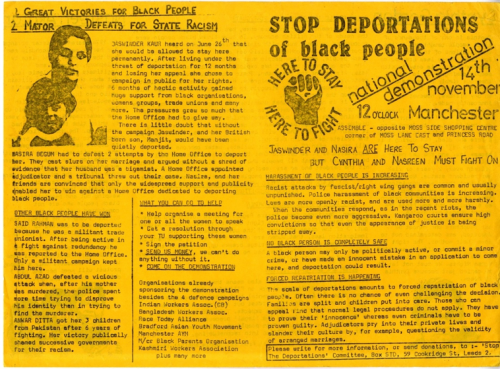

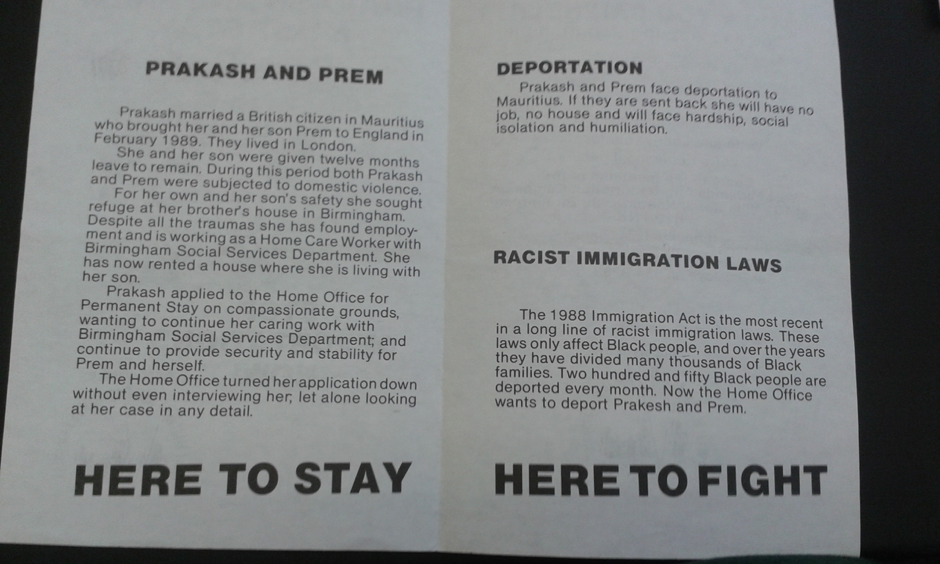

Looking at the arguments of anti-deportation activists during the period from the late 1970s to the mid-1990s can help us better conceptualise the relationship between deportation, discrimination and mobility. During this time, activists argued that deportation constituted the enforcement of discriminatory immigration controls. Slogans such as ‘British immigration laws are racist and sexist’ were repeated across the publicity material of various campaigns, making connections among racial and gender forms of discrimination.

Leaflet from ‘Prakash and Prem Must Stay’ Anti-Deportation Campaign, Birmingham [1993]

Some of the activists I interviewed believed that during the 1970s and 1980s the British state had introduced a series of measures – including visa restrictions towards particular countries, carrier sanctions and particular immigration policies – that curtailed the mobility of racialised populations. Many activists argued that the specific immigration laws introduced at the time, most prominently the 1971 Immigration Act, were designed to be discriminatory.

Other participants believed that immigration controls were mainly discriminatory in their effects. They argued that racialised minorities were disproportionately targeted in the enforcement of such laws, as a result of both institutionally racist institutions – e.g. the police, the criminal justice system and Home Office – and the prejudices of individual officials.

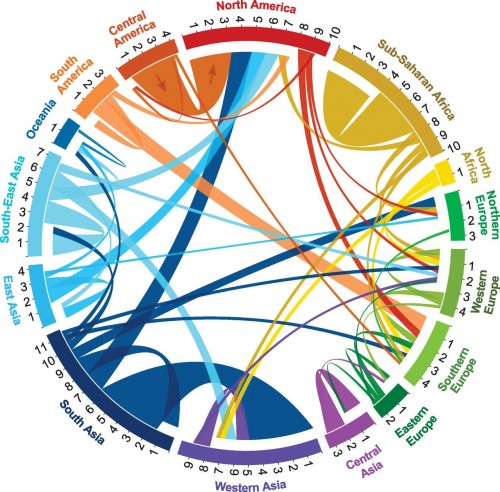

While today immigration controls are not explicitly discriminatory, the same measures that were introduced in the 1980s to prevent access to the territories of Northern states – such as restrictive visa regimes – are still in operation. They affect disproportionately, though not exclusively, poor countries where the majority of the population is black. This observation allows political theorists to make more structural and historically grounded critiques of how global access to mobility still operates across racial and socio-economic hierarchies, as some have already started to do.

Moreover, these historical examples highlight the importance of the discriminatory effects of immigration policies. The fact that members of the Windrush generation, that is black British people, were targeted by the latest immigration rules and that some were even wrongly deported, suggests that both scholars and practitioners should be more attentive to the possibilities of institutional racism arising at the level of enforcement.

Deportation and The Legacy of Colonialism

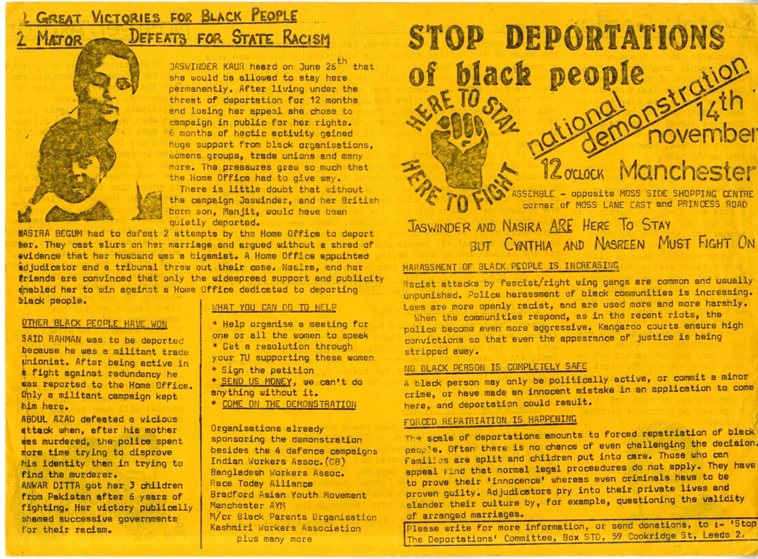

Encapsulated in the slogans ‘We are Here Because you Were There’ and ‘Here to Stay, Here to Fight’, the theme of British colonialism also played an important role in shaping the views of my participants.

Call for Demonstration: 'National Demonstration to Stop Deportations of Black People', Manchester [1981], Photo Credit: Tandan Archives.

Particularly for those second-generation migrants whose families came from Commonwealth countries in the 1950s and 1960s, colonialism was embroiled in their histories and memories. Some of my participants from India remembered how their grandparents fought for Britain during World War Two, only to later recount their experiences of racism while growing up in 1960s' Britain.

Furthermore, these participants regarded the imposition of immigration controls towards Commonwealth citizens in 1962, 1968, and 1971 as unfair because it unilaterally violated a freedom of movement agreement between Britain and India.

Appealing to the history of colonialism thus highlighted the injustice committed by the British state towards colonial subjects and their descendants across various historical periods: from outright subjection and exploitation during colonial times, to experiencing racism while settling in Britain, to facing unilateral restrictions to entry and settlement in Britain from the mid-1960s onwards. The Windrush scandal could be added as the latest event in this list of transgenerational injustices.

Taking seriously the legacy of colonialism enables theorists to develop arguments grounded on the special obligations that the British state has towards long-term migrants from its ex-colonies, as part of its recognition of and reparation for its past injustices, thus expanding existing arguments on behalf of asylum seekers.

Conclusions

Historical arguments of anti-deportation activists can help us rethink the controversies of deportation today by elucidating the relationship between mobility, discrimination and historical injustice. Deportation can reproduce some historically grounded injustices concerning both who has access to mobility and the rights of long-term migrants from ex-colonies, including that to secure membership. It also creates particular forms of discrimination at the level of enforcement.

Attuning one’s analysis of deportation to the process of discrimination is useful for assessing migration policy even in Post-Brexit Britain, such as by examining the effects of enforcement policies for white, but still racialised, European migrants. While since the 1990s the background of those subject to deportation has become increasingly diverse, migration scholars and practitioners should pay attention to less explicit, but equally insidious, forms of discrimination across cultural, religious and socio-economic axes.

This research was partially funded by the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs’ Research and Dissemination Fund.